During September of 2023 we will look at the Western Rite.

The Oxford Dictionary defines rite as: “a religious or other solemn ceremony or act. ‘the rite of communion.'”

A stricter definition used by liturgists is a rite is words that are spoken (or sung) in worship. Ceremony is actions or gestures used in worship.

The Western Rite isn’t a single rite, but more of a pattern of words and songs that many denominations and traditions follow. The Roman Catholic Mass, the Lutheran Divine Service or Gottesdienst, the Anglican / Episcopalian Eucharist are all variations of the Western Rite.

Some denominations / traditions consider the Confiteor / Confession a part of the service. Some consider it separate, with the service proper beginning with the Kyrie. This is why the opening / processional hymn is sometimes before the confession, sometimes after. Modern Roman Catholic usage sometimes combines the Confession with the Kyrie.

The confessional rite is based on the private prayers a priest would pray in preparation for the mass and while putting on vestments (Reed, p. 256). Among Lutherans, private confession was still used in the early years, and public rites of confession began to appear in the 1530s (Reed, p. 258). This is a relatively late addition to the Western Rite.

The invocation is the same phrase spoken at baptism–the words that connect us with God’s name. We approach our God as his people, baptized into his name, cleansed with Christ’s blood. The sign of the cross is also a reminder of baptism. “Receive the sign of the cross on the head and heart + to mark you as one redeemed by Christ the crucified.” The invocation also reminds us whose work we are here to do. We worship in God’s name.

This is how we approach our God. Like the father of the prodigal, our heavenly Father awaits us with open arms.

We hear God’s forgiveness proclaimed, again, because of the life and work of our Savior Jesus.

In the name of the Father and of the + Son and of the Holy Spirit.

Amen.

Beloved in the Lord! Let us draw near with a true heart, and confess our sins to God, our Father, asking him in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ to grant us forgiveness. (Hebrews 10:22)

Our help is in the name of the Lord,

the Maker of heaven and earth. (Psalm 124:8)

I said, “I will confess my transgressions to the Lord,”

and you forgave the iniquity of my sin. (Psalm 32:5)

Almighty God, merciful Father, I, a poor, miserable sinner, confess to you all my sins and iniquities with which I have ever offended you, and justly deserved your temporal and eternal punishment. But I am heartily sorry for them, and sincerely repent of them, and I pray of your boundless mercy, and for the sake of the holy, innocent, bitter sufferings and death of your beloved Son, Jesus Christ, to be gracious and merciful to me, a poor, sinful being.

Upon this your confession, I, by virtue of my office as a servant of the Word, announce the grace of God to all of you, and in the stead and by the command of my Lord Jesus Christ I forgive you all your sins, in the name of the Father and of the + Son and of the Holy Spirit.

Amen.

Source: Saxon Church Order of 1581, translation based on The Lutheran Hymnal, 1941. For German original, follow this link.

There are many forms of confession and absolution. We confess what we are. We confess what we have done. We know what we deserve and what we would get if we approached a holy God alone. We are not beating ourselves up–we are stating facts. Here is another fact: Jesus Christ suffered and died to bear our sin and take it away. We plead for God’s mercy for the sake of Christ.

In the ancient church, an introit was sung at this point. Introit means entrance. Most introits were short chants composed from psalms or other parts of Scripture, concluding with the Gloria Patri and then repeating the opening verse. Here is the introit for the first Sunday in Advent:

Antiphon:

To you, O Lord, I lift up my soul.*

O my God, I trust in you; Let me not be ashamed;

Let not my enemies triumph over me.*

Let no one who waits on you be ashamed. (Psalm 25:1-3a)

Psalm:

Show me your ways, O Lord;*

teach me your paths.

[For you are the God of my salvation;*

on you I wait all the day.

Let integrity and uprightness preserve me,*

for I wait for you.

Redeem Israel, O God,*

out of all their troubles.] (Psalm 25:4-5, 21-22)

Glory be to the Father, and to the Son,*

and to the Holy Spirit;

as it was in the beginning,*

is now and will be forever. Amen.

Antiphon:

To you, O Lord, I lift up my soul.*

O my God, I trust in you; Let me not be ashamed;

Let not my enemies triumph over me.*

Let no one who waits on you be ashamed. (Psalm 25:1-3a)

Source: Sanctus, November 27, 2022. Psalm 25:5 and 21-22 are not part of the original Introit.

Martin Luther suggested a spiritual song or a psalm be sung in German instead of the introits (https://history.hanover.edu/texts/luthserv.html, also Luther Reed in The Lutheran Liturgy, p. 262). It is likely he reccommended this because the introits were fragments, and the thematic connection with the readings was sometimes unclear. Much earlier in church history, the practice of singing whole psalms as entrance hymns or as interludes between Scripture readings was widespread (Reed, p. 261) .

Some churches sing an entrance hymn here. Some sing it before the invocation.

The Kyrie originally had the form of a short litany. Here is Kyrie, Orbis Factor, one of nine Kyrie litanies used in Sarum which can be viewed at this link.

Maker of the world, King eternal,

have mercy on us.

Fount of boundless pity,

have mercy on us.

Drive away from us all that is harmful,

have mercy on us.

Christ, the Light of the world, giver of life,

have mercy on us.

Look on those wounded by the craft of the devil;

have mercy on us.

You preserve those who believe in you, and you strengthen them,

have mercy on us.

Your Father, you, and the Spirit proceeding from both,

have mercy on us.

We know you to be one God, and three persons,

have mercy on us.

Be present with us, Counselor, that we may live in you,

have mercy on us.

Source: The Sarum Missal in English, Part II, Alcuin Club Collections, No. XI

Another Kyrie litany, taken from the fourth century Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, is in wide use today among Lutherans:

In peace, let us pray to the Lord.

Lord, have mercy.

For the peace from above,

and for our salvation,

let us pray to the Lord.

Lord, have mercy.

For peace to the whole world,

for the well being of the Church of God,

and for the unity of all,

let us pray to the Lord.

Lord, have mercy.

For this holy house,

and for all who offer here their worship and praise,

let us pray to the Lord.

Lord, have mercy.

Help, save, comfort, and defend us, gracious Lord.

Amen.

From Lutheran Book of Worship, 1978.

The more basic three, six or ninefold Kyrie is a remnant of the earlier Kyrie litanies (Reed, p. 269).

Kyrie eleison.

Christe eleison.

Kyrie eleison.

Lord, have mercy.

Christ, have mercy.

Lord, have mercy.

The purpose of the Kyrie at the beginning of the service, long or short, is to cast all our cares and needs before the Lord. The common Kyrie above (“In peace let us pray to the Lord…”) has the repeated theme of peace. Jesus said, “My peace I give to you. Not as the world gives do I give to you” (John 14:27). The Means of Grace, the gospel in Word and Sacrament that we are about to receive, are the only place we will find the peace we seek, because there alone we find Jesus, his Word, his forgivness, his restoration and peace.

The Gloria in Excelsis is the main song of praise in the Western Rite. It came from the Greek church as a song used in Morning Prayer / Matins as early as the second or third centuries. By the 500s it started to be used in the western church, first in the main service at Christmas, then at other high festivals, and then in regular usage.

It begins with the song of the Christmas angels:

Glory to God in the highest,

and peace to his people on earth.

Many consider the first two lines to be an antiphon, and in modern practice, it is often used as a repeated refrain. Originally the officiant would chant the first line, “Gloria in excelsis Deo” (“Glory to God in the highest”) and the congregation would join in the rest, “et in terra pax…” (“and on earth peace…”). This is why the Gloria is sometimes referred to as “Et in terra…” (And on earth…”)

The song of the angels has a parallel structure to it. The ELLC’s translation brings it out very clearly. In the birth, life, and work of Christ, glory is given to God. Peace is given to people.

The first stanza of the song is directed to God the Father, and praises God for who he is:

Lord God, heavenly King,

almighty God and Father,

we worship you, we give you thanks,

we praise you for your glory.

The second stanza is directed to God the Son, and praises him for both who he is and what he does. The second stanza also has the character of the Kyrie, “Have mercy on us.” “Receive our prayer.” Ancient songs and psalms sometimes put the central thought in the center of the song, and here is the center of the Christian faith: Jesus Christ is the Lamb of God who bears our sin.

Lord Jesus Christ, only Son of the Father,

Lord God, Lamb of God,

you take away the sin of the world:

have mercy on us;

you are seated at the right hand of the Father:

receive our prayer.

The third stanza brings the song to its highest point, again praising God for who he is. The third stanza is trinitarian, emphasizing that we worship one God, one Lord, who is Most High, revealed as “Jesus Christ, with the Holy Spirit, in the glory of God the Father.”

For you alone are the Holy One,

you alone are the Lord,

you alone are the Most High,

Jesus Christ,

with the Holy Spirit,

in the glory of God the Father. Amen.

The Gloria in Excelsis is very credal. It confesses truths about God, his attributes, and his works.

The Gloria is often omitted during Advent and Lent. That tradition came about as a fast for the ears in preparation for the exuberance of Christmas and Easter.

Among Lutherans it may be replaced by the Canticle “Worthy is Christ” / Dignus est agnus during the Sundays of Easter.

Refrain:

This is the feast of victory for our God.

Alleluia, Alleluia, Alleluia.

1 Worthy is Christ, the Lamb who was slain,

whose blood set us free to be people of God. [Refrain]

2 Power, riches, wisdom and strength,

and honor, blessing and glory are his. [Refrain]

3 Sing with all the people of God

and join in the hymn of all creation.

4 Blessing, honor, glory and might

be to God and the Lamb forever. Amen. [Refrain]

For the Lamb who was slain

has begun his reign. Alleluia. [Refrain]

© 1978 Lutheran Church in America, The American Lutheran Church, The Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada, and The Lutheran Church – Missouri Synod

The Gloria had this thought at the center: “Lord God, Lamb of God, you take away the sin of the world: have mercy on us.” The canticle Worthy is Christ is taken from phrases in Revelation 5, 15 and 19, and praises Christ as the Lamb who was slain, who made us his people by his blood, and lives and reigns over his church.

he Celts were a people and a culture, and they seem to have been in central Europe as early as 800 B.C. (Sometimes called the Hallstatt Culture.)

he Celts were a people and a culture, and they seem to have been in central Europe as early as 800 B.C. (Sometimes called the Hallstatt Culture.)

efore Christian missionaries came to the Ireland, the Irish Celts were polytheistic (many gods) and animistic (belief of spirits in everything, people, plants, animals, trees, etc.), which is the source of the idea that Druids (Celtic priests) worshiped trees. Christian missionaries came into Britain after Christianity was decreed a religio licita, a legal religion, and also the religion of the Roman Empire, with a peak of missionary activity in the fifth century.

efore Christian missionaries came to the Ireland, the Irish Celts were polytheistic (many gods) and animistic (belief of spirits in everything, people, plants, animals, trees, etc.), which is the source of the idea that Druids (Celtic priests) worshiped trees. Christian missionaries came into Britain after Christianity was decreed a religio licita, a legal religion, and also the religion of the Roman Empire, with a peak of missionary activity in the fifth century.

rom the time of Patrick (d. ca. 460) until the Synod of Whitby in 664, the Celtic church was independent of the church of Rome but did not see itself as separate from it. This was also the golden age of Irish monasteries which were centers of faith and centers of learning, both sacred and secular. Missionaries were sent out, first back to Britain, Wales and Scotland, then to mainland Europe. Traveling monks established churches and monasteries. There was a difference between the Irish churches and the churches of Rome. The Irish calculated the date of Easter with a different formula—usually resulting in celebrating their Easter a week or two after Roman Easter. Irish monks had their own tonsure (either a wedge-shaped stripe was shaved over the top of the head from ear to ear, or the front of the head was shaved to a midline from ear to ear), while Roman monks had a coronal tonsure (like Friar Tuck with a wreath of hair around a bald dome). The Irish churches had their own rites with service outlines similar to the Roman mass and liturgies of hours, but with unique prayers. Celtic churches did have a veneration of saints, but it was mostly honor for deceased bishops and abbots, along with the biblical New Testament saints. Some of the prayers ask the saints, “Pray for us.” In pre-Whitby literature, Mary is mentioned as the mother of the Lord, but gets no special honor. After the Synod of Whitby, the Celtic churches in Ireland, Scotland, Wales and all their missions were ordered to calculate the date of Easter in the Roman manner, and to adopt the Roman tonsure and other worship practices. From that point, the Celtic church began to lose its distinctiveness from the church of Rome, although some unique practices and emphases continued.

rom the time of Patrick (d. ca. 460) until the Synod of Whitby in 664, the Celtic church was independent of the church of Rome but did not see itself as separate from it. This was also the golden age of Irish monasteries which were centers of faith and centers of learning, both sacred and secular. Missionaries were sent out, first back to Britain, Wales and Scotland, then to mainland Europe. Traveling monks established churches and monasteries. There was a difference between the Irish churches and the churches of Rome. The Irish calculated the date of Easter with a different formula—usually resulting in celebrating their Easter a week or two after Roman Easter. Irish monks had their own tonsure (either a wedge-shaped stripe was shaved over the top of the head from ear to ear, or the front of the head was shaved to a midline from ear to ear), while Roman monks had a coronal tonsure (like Friar Tuck with a wreath of hair around a bald dome). The Irish churches had their own rites with service outlines similar to the Roman mass and liturgies of hours, but with unique prayers. Celtic churches did have a veneration of saints, but it was mostly honor for deceased bishops and abbots, along with the biblical New Testament saints. Some of the prayers ask the saints, “Pray for us.” In pre-Whitby literature, Mary is mentioned as the mother of the Lord, but gets no special honor. After the Synod of Whitby, the Celtic churches in Ireland, Scotland, Wales and all their missions were ordered to calculate the date of Easter in the Roman manner, and to adopt the Roman tonsure and other worship practices. From that point, the Celtic church began to lose its distinctiveness from the church of Rome, although some unique practices and emphases continued. t. Patrick’s Breastplate is a poetic prayer that is attributed to Patrick. Like the winding lines in Celtic art, the content of the prayer seems to wind back and forth with its repetition. Here are some characteristics in the Breastplate that are common in many Celtic Christian prayers:

t. Patrick’s Breastplate is a poetic prayer that is attributed to Patrick. Like the winding lines in Celtic art, the content of the prayer seems to wind back and forth with its repetition. Here are some characteristics in the Breastplate that are common in many Celtic Christian prayers: ther Celtic prayer

ther Celtic prayer s:

s:

he Book of Kells (

he Book of Kells (

“Mozarabic” is really a term historians use for Christians who lived in Spain under Muslim or Arab rule. It literally means “among the Arabs.” The people never would have called themselves “Mozarabs.”

“Mozarabic” is really a term historians use for Christians who lived in Spain under Muslim or Arab rule. It literally means “among the Arabs.” The people never would have called themselves “Mozarabs.” Since the Mozarabic Rite developed its own rites and prayers for each Sunday and the liturgies of the hours each day there are a lot of prayers from the Mozarabic tradition out there. Since A Collection of Prayers is about meaning in prayers and gathering prayers that are rich in meaning, the Mozarabic Rite has become a favorite source. The chief source for Mozarabic prayers is the book

Since the Mozarabic Rite developed its own rites and prayers for each Sunday and the liturgies of the hours each day there are a lot of prayers from the Mozarabic tradition out there. Since A Collection of Prayers is about meaning in prayers and gathering prayers that are rich in meaning, the Mozarabic Rite has become a favorite source. The chief source for Mozarabic prayers is the book ![B_Escorial_93v[1].jpg](https://acollectionofprayers.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/b_escorial_93v1.jpg?w=277) Mozarabic Rite or Mozarabic Liturgy (this would include everything related to the worship of Mozarabic Christians.)

Mozarabic Rite or Mozarabic Liturgy (this would include everything related to the worship of Mozarabic Christians.)

![Lucas_Cranach_(I)_-_Johannes_Bugenhagen[1]](https://acollectionofprayers.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/lucas_cranach_i_-_johannes_bugenhagen1.jpg)

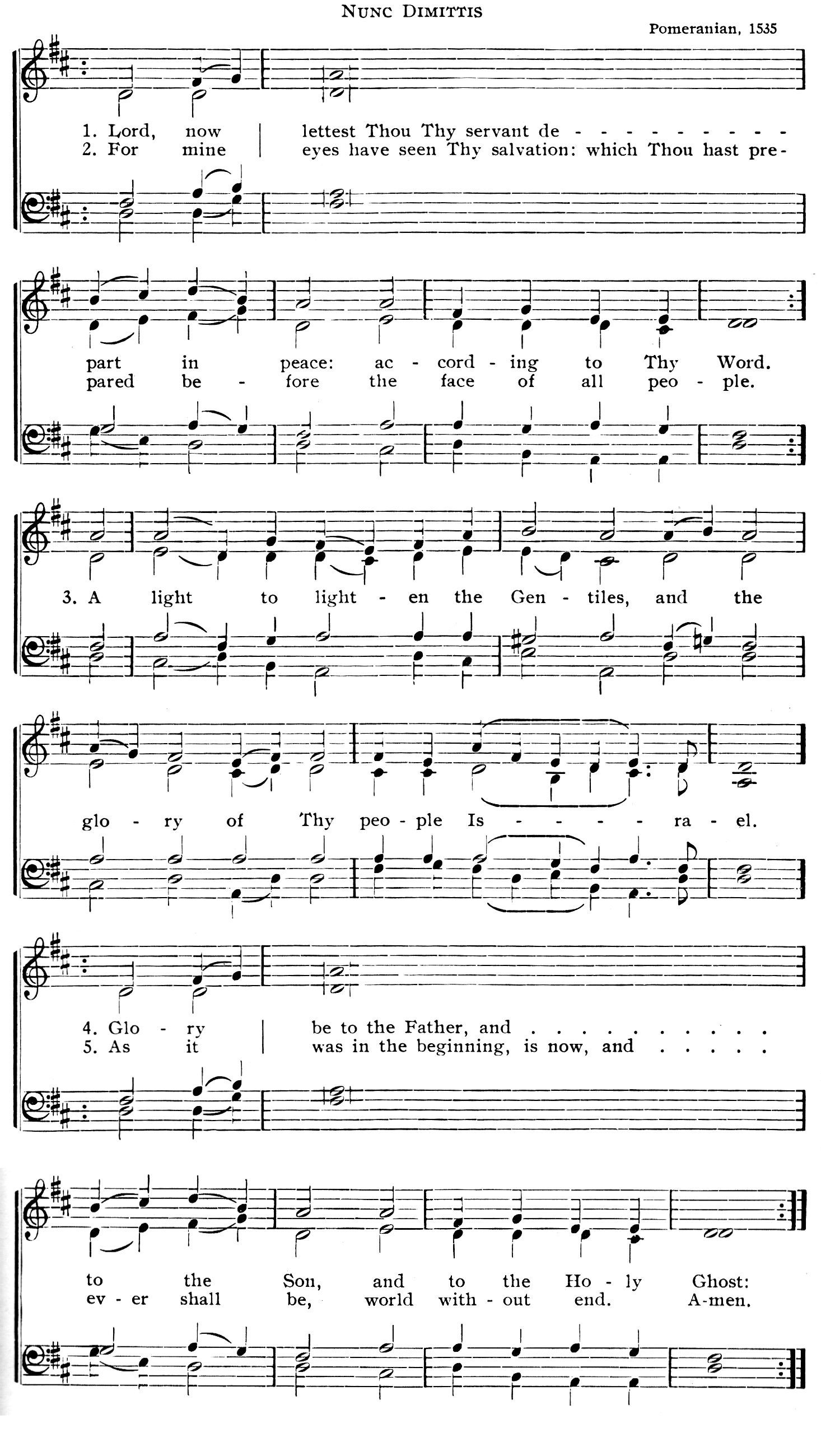

from Book of Hymns (WELS, 1920)

from Book of Hymns (WELS, 1920)